UK manufacturing is a sector beset with contradictions. One minute the forecast for growth is being downgraded to a contraction of 0.6%; the next Jaguar Land Rover announces that it is moving to 24-hour production to keep pace with demand, meaning a further 1,000 jobs at its Merseyside factory. And an increasing trend for UK firms to reject the offshore outsourcing models of the last decade to return production to Blighty’s shores adds to a rosy picture of UK manufacturing. But is it an accurate one?

There’s no denying that the uncertainty generated by tensions in the Eurozone has had a profound effect on commerce in the UK across the board – in terms of confidence, future outlook and, vitally, business investment. It seems reasonable, then – if unfortunate – that while the UK economy is expected to grow by 0.2% this year, manufacturing will shrink slightly. The manufacturers’ organisation EEF says that output in the first half of the year was particularly weak, with its forecast showing a contraction in the first six months.

“There is no doubt that conditions in the immediate term have become much more uncertain,” says Mark Swift, head of communications at the EEF. “The ongoing Eurozone crisis has knocked confidence sideways in Europe and is also having a knock-on effect elsewhere with growth in countries such as China slowing,” he continues.

However, the subdued nature of things shouldn’t last too long, he reckons. “The medium- to long-term prospects remain very positive for UK manufacturers as prospects for growth in the majority of emerging markets, including the Middle East and South America, look very strong.” The stats back this up too: the EEF’s figures show that manufacturing will be up to a more respectable 2.1% next year. And it makes sense that the appetite for British-made goods will continue: in the past five years, exports to China are up 185%, to Brazil up 172% and Russia 145%. This is far beyond the overall increase of 34%.

Currently, one of the hottest areas of development is in green industries. Not only are manufacturers taking their environmental responsibilities more seriously – two-thirds are either currently involved with, or plan to be involved with, the development of low-carbon technologies – but companies with a focus on making the world a cleaner, greener place seem to be thriving.

One such company is Closed Loop Recycling in Dagenham. Set up by Chris Dow and Rob Pascoe, it began operations in 2008 after a long, hard slog to secure the £17.5m needed to build the factory. Closed Loop is the UK’s first ever plastic bottle recycling plant – after it cleans and breaks down the bottles, they come out the other end as food-grade recycled PET, which is then sold on to companies such as Marks & Spencer and Coca Cola.

“We’re putting everything in place to give ourselves the best chance of recovery,” says MD Dow. “It’s pretty hard to be in the UK right now and not feel the optimism evoked by the Olympics.” The Olympics are one of the raisons d’être for Closed Loop: one of its initial aims was to make London 2012 the greenest Games ever. And the sports spectacle has given business a boost in more than one way: “The great thing about the Games was the learning experience. It was widely covered and the recycling facilities at the venues were excellent; this adds up to the possibility of making the Games a stepping stone to a higher recycling rate.”

What’s more, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg publicly praised Closed Loop as part of the Olympic Games legacy. The company is already undergoing another £12m expansion that will see it increase its plastics sorting capacity to more than 100,000 tonnes per year.

Manufacturing is getting a boost in other ways too. For myriad reasons, there is an increasing number of UK businesses that are opting to move production to Blighty’s shores. For example, Rob Law, inventor and founder of kids’ ride-on luggage-maker Trunki (see case study two), decided to move production from China to Devon when the benefits of manufacturing in the Middle East became negligible.

Trunki’s story is indicative of a wider trend says the EEF’s Swift. “There are a variety of reasons [for the shift]. These include the fact the cost differential with places such as China is not as great as it once was, the cost of transport has increased, tougher regulations in areas such as environmental legislation are placing an onus on suppliers, which some emerging economies cannot meet, plus there are also now increasing demands from major manufacturers to have their suppliers close by,” Swift explains.

All things considered, the outlook isn’t too shabby at all. The overall message seems to be that things may get worse before they get better – but what’s important is that they will indeed get better. The EEF says there has never been a more important time to keep the spotlight on UK manufacturing. And, of course, it’s right. The success of the internationally respected ‘Made in Britain’ label is vital to re-establishing stability in the UK economy.

Case study 1

Cambridge Satchel Company – Founded by Julie Deane

From the very beginning, I was adamant that our bags had to be manufactured in the UK. Because, to me, a school satchel is a very British thing. And there were other reasons, too. From a purely practical point of view, I didn’t have a background in manufacturing or retailing. It’s therefore a lot easier for me to sit down and talk to someone over a desk and to completely understand them with no language barrier.

The other great thing about working with manufacturers in the UK has been that in the early days, I could order just six of a certain type or design. They never said it has to be 50 or 100. That means I could keep investing as I sold and gradually build it up.

I think people like to buy British products, too. They gain a sense that they are helping with the economic recovery. I certainly look at where something has been made when I buy it. There’s something really nice about thinking, ‘I’m investing in something that is going to create more jobs in this country.’ The money we spend on products made overseas is like a vote for Asian manufacturing – so we can’t be surprised when factories close and people are out of work. People aren’t that naive.

The other thing is that we have such an incredible connection with the product. When the bags are delivered to our Cambridge headquarters we look at them, and we know the people who have done every single process along the production line. There’s something very satisfying about that.

Case study 2

Trunki – Founded by Rob Law

When I was writing my business plan in 2005, we were getting costs from Eastern Europe that were the same as we needed to sell the products at. It was much cheaper to make Trunkis in the Far East, so that’s where we set up manufacturing.

Then, 18 months ago, there were quite a lot of changes in the business conditions. The cost of shopping was going through the roof, and with Trunki being quite a large product, landing costs were very high too. Manufacturing over in the Far East meant we’d need to put in large orders for peak seasons, such as summer and Christmas, 128 days in advance of when we needed them, which ties up a lot of our cost flow.

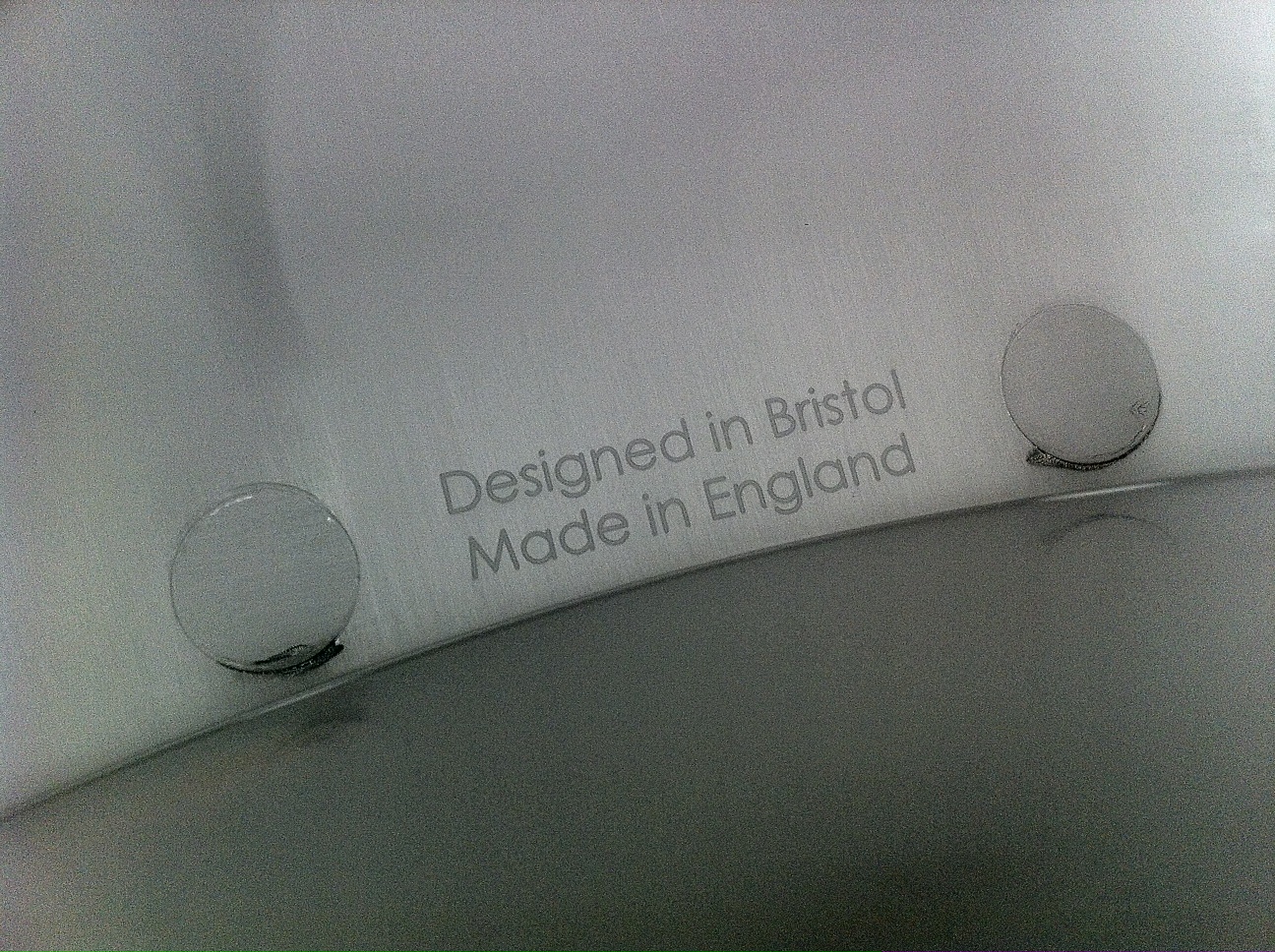

So factoring in these issues, I thought it would be worth looking again at UK production. We found a great company down in south-west England called Inject Plastics, and the first UK Trunkis rolled off the production line on 6 May this year – which was also our sixth birthday.

We’ve never had a problem with quality, but the factory is certainly more accessible now – our design teams can just pop down there rather than taking 24 hours to travel to China. This makes us much more dynamic and flexible in adapting to our changing customer needs. So, if there is a particular trend – say for the Olympic-special Trunkis – we could just make them. If we’d still been in China we would have had to bring over a shed-load of containers and then just pray to God that they were going to sell.

There’s a real trend emerging around onshoring. I think for the boom years it was all about cost – trying to get the cheapest possible product. That has changed.

Share via: