The arts and crafts movement first emerged during the late Victorian period in the wake of industrialisation. Speaking of the movement’s imminent demise in 1903, the American women’s rights activist, Mary Dennett wrote: “The modern man, who should be a craftsman, but who, in most cases, is compelled by force of circumstances to be a mill operative, has no freedom.” Instead she saw men who were compelled to make whatever the machine dictated. Seeing the potential of technology, Dennett had a vision that if mankind could harness electricity and make it more readily available, then the “emancipation of the craftsman and the unchaining of art” would come naturally.

While technology didn’t emancipate us all from the toils of labour to the extent Dennett imagined, there is now in 2014 a real movement of innovation in small business manufacturing that allows people to swap their jobs in the City for more creative and worthwhile pursuits in tech. Many startups are unlocking the hidden potential of creation found in computer technologies and hardware design typically reserved for larger companies. With this technology becoming cheaper, more readily available and easier to use, the time is right for this movement of small actors to grow.

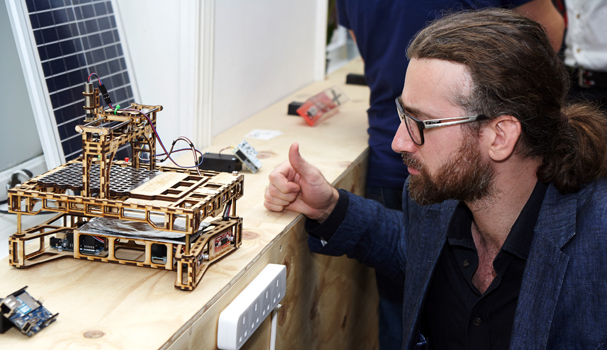

This is a movement built on an ethos of self-reliance, open-source learning, contemporary design and powerful personal technology like 3D printers and laser cutters. For those brave few it makes it much easier to set up a business and make stuff. The maker movement is a compendium of independent inventors, designers and even some chancers. Incubated in home studios and garages, it is a space where the artisan meets the computer whizz. At heart, it is a community in constant collaboration, seen most prevalently at mass workshops and hands-on events like Maker Faire, a playground for DIY tech enthusiasts.

Movers and shakers

While the maker scene in Silicon Valley is more mature and that of the UK is still in its infancy, we are quite the child prodigy. More entrepreneurs are taking bigger risks, more talent is emerging and Tech City is receiving more investment for the maker community. Fab Lab is just one example of a small-scale workshop allowing individuals to fabricate their own physical and digital products with access to the latest technologies. It began at MIT in 2001 and now has more than 350 spaces around the globe and a growing presence in the UK. In September, Andrew Gregson and Tony Fish took it upon themselves to start Fab Lab London. As Gregson, who is also the director, puts it: “We’re carrying the torch for personal fabrication.”

With the mind-boggling array of tools on offer, Fab Lab London is to tech what Willy Wonka’s factory is to candy. It has robots, quadcopters, homemade laser cutters, a £30,000 laser cutter, milling machines, 3D printers, Arduinos, Raspberry Pis, Intel Galileo boards, sensors and more. And it isn’t just for those who already have the skills to use these technologies; it is open to anybody who wants to make something. “There is a whole range people from different backgrounds who want to use these tools either for personal use or to start a business,” says Gregson.

Fab Lab London already has a few startups interested in working in its space. “These guys know about electronics and how to build some of the hardware but just need a place to do larger scale projects,” says Gregson. The technology is so accessible a child could learn it – and they are. Gregson and his team also work with school children aged 10-15. “Kids want to know what this is all about and Fab Lab gives them a sense of the realms of reality.”

Gregson is an enabler in the best possible sense. He believes this movement is “part of the natural evolution of technology” which is being driven by a combination of things, including the need for change and a real consciousness around sustainability. “Whether it’s the climate, water issues, a lack of food, it has almost come full circle back to the grassroots to try and make positive changes.”

Fab Lab isn’t so much ‘do it yourself’ as ‘do it together’. “There is a whole spirit of collaboration within the maker network and people are always trying to assist each other, whether that’s sharing skills or helping each other out with products,” says Gregson.

Labour of love

The maker movement is headed by innovative individuals seeking a creative outlet or who have grown tired of mass production, monotony and made-in-China labels. Knyttan is a startup pioneering the democratisation of manufacturing, giving people the opportunity to design the things they buy and collect them locally. This “experimental factory of the future” begins operations on November 4 at Somerset House in London. Co-founder Ben Alun-Jones and his team have found a new way of using industrial knitting machines; the same machines used by big names like Burberry Louis Vuitton to make their knitwear. “As the software controlling these machines is very old fashioned and complicated, we’ve gone back to the base level and rewritten it so that the machine can be controlled without any knowledge of how it works.” Designs are created and edited in a web browser, tablet or smartphone, sent automatically to the machine and out comes the customised product.

Instead of workers being dictated to by machines as Mary Dennett saw in her day, ordinary individuals can now tell the machines exactly what they want. Consumers are expecting more personalisation and control with the products they buy and this is exactly what Knyttan provides. “We allow you to control each individual stitch as if were a pixel on a screen, which then forms an algorithmic pattern you can tune to make your jumper louder or more subtle – it’s up to you,” says Alun-Jones.

“There is a movement of people at home playing with things and re-engaging with the idea of making and once it starts to impact on industry things will really change,” he says. “Making use of technology in this way is quite disruptive and the idea of connecting to your product has many possible outcomes.”

While mass production has given many an abundance of clothes and food, it produces an awful lot of waste. “Having a more customised approach and overall a higher quality product is a much more sustainable way to operate,” he says.

The idea of customisation runs through the entire movement. WonderLuk, a 3D-printed jewellery company, is a proud pioneer in the revolution taking place in the fashion industry. 3D printing communities are often perceived to be male dominated but this venture is headed by CEO Roberta Lucca who co-founded WonderLuk with COO Andre Schober in July 2013. Items are one-offs made exclusively for customers in the colour, material and size they want.

“The vast majority of products out there are mass produced – they are everywhere,” says Lucca. This serial entrepreneur started the company in response to so many people asking her where she gets her jewellery from. “I was always on the hunt for very individual accessories.” Having come across 3D printing she saw how it could be applied to custom-made products.

People with a strong sense of individuality want their own designs and their own ideas to be the basis of the items they wear, says Schober. “The appetite for individuality is immense because people are so tired of having to consume what the high street dictates they consume,” he says. “We put a lot of care into our work and quality assurance is something we are very particular about.”

WonderLuk works with various designers. “If they create something really amazing, through us they have a great showcasing platform and an outlet to commercialise,” says Lucca. They key thing with 3D printing is the speed with which you can create things in-house. And as the cost is a fraction of what it used to be, makers can swiftly and cheaply put together a prototype, test it and improve on it.

Lucca’s company has just closed a £150,000 round of seed funding from Symvan Capital. It is now looking into working with metals like gold, titanium and silver. “It is looking really promising and with this funding we are hoping to also expand our network of designers and expand into new markets also,” says Lucca.

Gaining momentum

Empowerment of individuals and communities is a key theme in the maker movement. Those who take the leap and start their own companies are very happy to have the chance to work in a creative environment that is both innovative and profitable. Silicon Milkroundabout runs regular events designed to match talented people with the thousands of jobs on offer at UK tech startup. A promotional poster for one of their get-togethers read: “Don’t work for the suits – work for a startup.” It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to imagine a future poster reading: “Don’t work for the suits – join the manufacturing revolution.”

As with all movements, it’s the grassroots that drive the maker movement forward; people like Rachael Howard, founder of Owl and Otter, a maker business run from sunny Brighton. She uses a laser cutter to make clocks, broaches and cutting boards. “We’re really committed to making practical and stylish homeware products and we love embracing new technology,” she says.

As is the norm in this movement, Howard is environmentally conscious. She works with bamboo, which grows at a rate of one meter per day. “It isn’t just sustainable but is lightweight and has a beautiful grain,” she says. Owl and Otter operates in the UK but also ships to Australia, America, Brazil, Mexico and Hong Kong. “It’s a high quality product and I feel proud of that.”

Like WonderLuk, Owl and Otter is part of the growing online community for selling makers’ wares. Etsy is full of outlets using all of the technology in question to make crafty things in a new way. A decade ago this kind of business would not have been possible, but thanks to Etsy – and others like Folksy – it is a wholly viable industry. True to the collaborative nature of the maker movement, Owl and Otter is also part of various local groups in Brighton that work together, offer support, share ideas and help promote each others’ products.

Former charity worker Howard started Owl and Otter in 2012 after being made redundant in the recession. “We wanted to secure our future a little bit more and having a creative outlet was really refreshing,” she says. Following the downturn, people wanted to earn an income and have a bit more control over their lives, she says. “Having access to new technology in the manufacturing process is quite liberating; it means you have much more flexibility and don’t have to be stuck in the traditional nine to five.”

Companies like Owl and Otter will not remain well-kept secrets for long and Howard is a prime – albeit a little belated – example of the kind of emancipation Mary Dennett was talking about more than a century ago. History is littered with examples of science fiction becoming reality and in the era of the maker movement the only limits are those of the individual’s imagination. Where would we be today if, instead of selling us with cars, Henry Ford sold us the means to produce our own? Viva la revolución!

Puppet master

Popagami

It was whilst working as a teacher in Seoul, South Korea that former security engineer Brian Smith came across an origami rabbit. “I was making these at a pre-school. Pokemon was big at the time and when I created my own version of Pikachu the kids loved it.”

As there was nothing else like this around, Smith started Popagami in 2002 with the aim of bringing the 17th century Japanese paper folding art of origami into the 21st. “Since starting I’ve been putting photographs onto them with programmes like Photoshop and kids can also design their own on the page.”

Realising the potential of modern technology for customer interaction, he has developed an app that makes the process easier. “You can personalise your own designs with photographs or even use it to create a digital 3D avatar in the style of Popagami,” says Smith. “This technology is not too expensive so as a very small basis you can actually produce an awful lot of products very quickly.”

Speaking of the maker movement, Smith says that it is now simpler than ever to connect to people through the various networks and communities and from a garage in West Sussex to go global without relying on bigger players. “It’s quite a powerful thing,” he says.

Popagami also creates children’s books. Keeping to the spirit of collaboration, Smith has created a book of origami puppets for the World Wildlife Federation and is in talks with children’s writers about doing something similar, including Julia Donaldson, author of the popular book, The Gruffalo. “The idea is to make these products more popular with these puppets,” says Smith.

With this increased interest, Smith recently left his job as a technician at a school in West Sussex to take Popagami full time. ![]()

Share via: