There’s no denying that the array of beers on offer at the local pub has exploded in recent times. At one time drinkers were limited to a few select brands; now there is an almost overwhelming variety of different beers to choose from. Craft brewing has opened the market up to a whole host of start-ups eager to tickle consumers’ tastebuds with innovative new brews.

But what’s been behind the massive surge we’ve seen in craft beer? The increasing popularity of craft beer has in part been driven by a growing dissatisfaction with the homogenisation of the market. Particularly amongst the younger generations, disillusionment with the lack of variety on show has led to a real demand for novel and authentic products. “They’re attracted to doing something more artisanal because they’ve all grown up with the banality of having just a few big global brands in the market,” says beer writer Pete Brown. In this light, the craft movement can be viewed as symptomatic of an age where consumers are increasingly on the hunt for the genuine article.

Creative craft

An interesting quirk of craft beer is that its definition is hotly contested. Thus one of the biggest questions when trying to understand the craft industry is ‘what makes a beer craft?’. “It’s totally subjective,” says Brown. “It means something completely different to everyone.” While some claim that it’s the preserve of smaller brewers, others have questioned whether there is significant overlap with the real ale movement. But the one thing that most can agree on is that craft brewing is driven by passion. “For me, the dividing line as to whether it’s craft or not is about attitude and approach,” Brown says.

And there does seem to be another consensus amongst brewers, consumers and journos alike: craft is synonymous with creativity. “Every craft brewery is always trying to make the perfect beer, which none of us are ever going to do,” explains Paul Seiffert, director at Liverpool Craft Beer. This endless striving for perfection has driven brewers to continually reinvent their ales and find new flavours that will give their brews the edge over the competition; similar to how tech start-ups are constantly tweaking their apps. “That passion and innovation is running throughout the entire industry,” he says. “We have to produce new and exciting things because we don’t want to become stale or stagnant.”

But there’s another ingredient that is helping to drive experimentation in the craft industry: the increasing variety of hops on offer. “One of the most interesting things about beer at the moment is the hop varieties that people use,” says Andy Moffat, owner of Redemption Brewing. Given the majority of craft brewers are looking west to what’s been happening in the States, it’s hardly surprising that many of them have been importing interesting new strains of hops from America, as well as the southern hemisphere. “They’re much higher aroma, much higher flavour,” he says. “Having access to those hop varieties has been one of the things getting brewers experimenting.”

Agile ales

Aside from an addiction to innovation, craft brewers share something else in common with their start-up brethren: an agile mindset.

While one might think that an industry so reliant on industrial kit would be really capital hungry, it doesn’t actually take too much cash to get a new craft beer brand off the ground. “A lot of the equipment you use in brewing is fairly simple; it’s a bit of stainless steel, a pump, some hose,” says Moffat. “It is possible to start cheap and brew really good beer.” Because of this, it’s easy for new brewers to bootstrap and get a product out to consumers without overheads creeping up too high.

Not only does this mean brewers can gradually scale up their operations as their needs require but this agility also makes it much easier to conduct market experiments to explore new lines. “We have a small brewery, a 100 litre exact replica of the large kit, which we roll out small batch stuff on,” says Seiffert. “This means we can make small batches and see what the response is before we plunge into a permanent new product.” Liverpool Craft Beer will often run small trials at closed tastings or festivals, finding out which beers go down best; this allows it to make the most of products that prove to be a hit and pivot on those that don’t.

This iterative approach enables craft breweries to run in a much more agile manner than their corporate peers, only putting real amounts of capital behind the brews they know will truly hit their mark. “Craft brewers should follow a lean methodology; don’t follow a product development where you’re committed to a set launch date,” says Matthew Denham, co-founder of UBREW, the open brewery that provides a shared space for new brewers to get started. By keeping things lean, craft brewers can grow their product range organically and ensure they’re committing only to lines that will be a guaranteed hit with consumers.

Of course, brewers aren’t forced to rely solely on this kind of agile, organic growth forever – there are more funding options available than ever for craft brands looking to accelerate their development. Not only are some brewers drawing in record figures through crowdfunding – just last month craft king BrewDog announced it would be extending its Equity for Punks to £25m – but traditional funding is also becoming increasingly viable. “Craft beer is very much a public thing now and there are a lot more funding streams available,” says Seiffert. “People are willing to throw a lot more money at it now because it’s fashionable.”

Craft a community

Previously, beer would have only been fashionable to a very specific demographic. “Beer used to be considered something that beardy, middle-aged men drank,” says Brown. But the face of the stereotypical beer-drinker has changed in recent years. “Craft has gotten a new generation excited about beer,” Brown adds. “Now all ages and demographics are drinking it.” During his career, Brown has seen audiences at industry events change massively; there has been a huge spike in younger drinkers and increasing numbers of women are being attracted to craft brands.

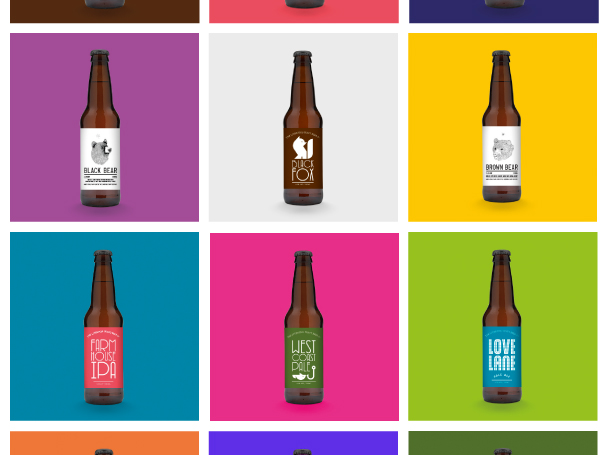

This is one of the reasons that branding has become increasingly important for craft brewers looking to cement their place in consumers’ hearts. Given drinkers of craft beer are more brand savvy, it has become vital for brewers to communicate just what they stand for. “Your branding – the culture of your brewery and what you stand for – it’s important to get those issues out there,” says Moffat.

In addition to this, the changing nature of the average beer drinker means the old-fashioned branding that often once accompanied traditional ale brands is unlikely to hit its mark. “You need to understand who you’re appealing to: a modern drinker is not going to want a half-naked woman on their beer bottle or pump clip,” Moffat says.

Given the increasing importance of brands in the craft space, it shouldn’t be much of a surprise that many brewers have turned to social media to foster connections with their customers. “Social media means people can see the brand, talk to us and get a feel for what we’re doing,” says Richard Burhouse, co-founder and managing director of Magic Rock. One of the attractions of craft beer is having a more fundamental connection to the people brewing your beer and the intimacy provided by social media can help consumers feel part of a brewery’s community. “The whole point of social media is to hear a [business’s] true voice isn’t it?” he says. “It’s feeling that you’re actually connected to the people that are running it.”

But this sense of community extends far beyond the online world. The rise of local craft breweries operating right in the consumer’s backyard has revived the centuries old tradition of the brewery being at the heart of the community. “Because of the historical role of beer and the pub in the UK, the local brewery is an important part of the community fabric,” says Moffat.

Whilst many craft brewers have a significant international profile, the rise of microbreweries and brewpubs in local communities has helped reignite an interest in what is being brewed right on consumers’ doorsteps. “We have brewers that brew locally and then take it back into their communities,” says Denham. “It’s one of my favourite pastimes: exploring these little communities and finding out where the microbreweries are operating.”

Pint-sized versus King-sized?

Much of the discussion around the craft movement focuses on the contributions of smaller brewers but there’s simply no denying that craft brewing is increasingly becoming big business. Denham points out that in the US, craft makes up somewhere around 2% of the total market. “It seems like a tiny share but, to those who are watching, it is still a significant percentage,” explains Denham. Inevitably large-scale brewers will be wondering how they can get in on the act.

There is already some clear interest from the larger players – some breweries have even launched their own ‘craft’ range. “They’re thinking: ‘let’s just do some cheeky branding, throw some weird ingredients in and people will love it’,” says Burhouse. But brewing with such a cynical attitude typically doesn’t produce stellar results; focus groups aren’t the best way to create a product that is supposed to be artisanal in nature. “The beers tend to be lacking in character,” he says. “I don’t think anyone who is a proper beer fan is fooled by it.”

This is one reason craft is an industry in which smaller brewers tend to shine. “It offers a smaller space to try out ideas,” says Brown. “It takes big brewers something like two years to develop flavour concept but it takes a craft brewer four days.” By way of example, he points to Magic Rock’s head brewer Stuart Ross; when he was working at the Crown Brewery, he came across a job lot of reduced chillies. “A week later he was bottling a chilli porter,” he says. “That kind of thing is a £250,000 innovation pipeline development for a larger company.”

So, taking this into account, how can a craft brewer keep the start-up spirit alive even as it grows? Seiffert feels that actually size is immaterial if a brewer can hold true to its roots. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a tiny brewery or a huge brewery,” he says. He points to Sierra Nevada Brewing Company and Brooklyn Brewery in the States and Camden Town Brewery in London as brewers that have been able to scale and yet are undeniably craft in identity. “As long as brewers stick to their core values and produce good beer, that will continue to resonate,” he says.

Solid as a rock

Magic Rock

Magic Rock’s co-founders were hardly newcomers to the industry; managing director Richard Burhouse had previously started an online beer retailer, whilst head brewer Stuart Ross had been brewing for nearly a decade for Yorkshire brewers including Kellham Island Brewery and Acorn Brewery. Being fans of US craft brews, the duo wanted to bring a taste of American suds to British tastebuds. “US craft beers are very dependent on hop character – the aroma and flavour – and that dies as time goes on,” says Burhouse. “So if you were to make them fresh, you’d have a really good angle compared to the imports that were coming over.”

Branding has been a key consideration for Magic Rock. “Another thing that attracted us to the American brewing scene is that it didn’t seem to be aimed at old men with beards or flatcaps,” says Burhouse. “It was much more youthful and modern.” Rather than focus on fusty old branding, Magic Rock has been keen to take a new approach. It took inspiration for its name from the Burhouse family business – a wholesale importer of crystals, rocks and minerals that was based at the same site – in order to set itself apart from a traditional style brewery. “We were looking to differentiate ourselves from somebody who might be called Huddersfield Brewing Company,” he says.

Building on the international success of brews like Ringmaster and Cannonball, Magic Rock is now looking to move to larger premises in Huddersfield town centre. The reasoning behind the move is two-fold; firstly it will allow Magic Rock to install its own canning line. “And we’re also going to have an on-site taproom that will be open outside of brewery hours, five days a week,” Burhouse says. By boosting its capacity and allowing it to roll out a retail range, the move looks set to help Magic Rock really capitalise on its market lead.

Craft for the crowd

UBREW

Matthew Denham and Wilf Horsfall, the co-founders of UBREW, first met whilst working at Impact Hub Westminster, the incubator and accelerator for social entrepreneurs, and quickly realised they had a shared interest. “We wanted to build upon our passion for brewing good quality beer but didn’t have the facilities to do it,” says Denham. The co-founders realised that there was a gap in the market for a collaborative space that allowed fledgling and experienced brewers to work side-by-side. “We essentially took the mentality of a tech start-up incubator and applied it to craft beer,” he explains.

After finding a small pop-up space and a single brewing kit, the co-founders turned to crowdfunding to raise the £3,000 they needed to get UBREW off the ground. “About 72 groups of five people signed up and overfunded us by £12,000,” says Denham. Realising how much its brewers were invested in the vision, UBREW decided to grow its potential even further by allowing brewers to buy equity in the company. “We raised £112,000 by releasing 10% of our business to the crowd,” he says.

Currently the firm is looking at ramping up its operations so brewers can naturally scale; it already has 50 litre and 100 litre kits in place for fledgling brands to trial their beers. “We have a taproom here and a bottle shop in partnership with Ales by Mail, so every week we have a ready-to-go market where people can test their beers,” Denham says. It’s currently putting together a full-scale 1,000 litre kit that will allow successful beer brands to go for a full commercial release. “If their beer sells, they can scale up to the 1,000 litre and take it to the market for real,” he says. “That’s the future of it.” ![]()

Share via: