Space was once a frontier only superpowers like the US or Russia could afford to conquer. But today, small satellite startups smash traditional barriers to the cosmos for many industries and increasingly court funding in the process. For as well as providing spacetech solutions for Earth’s greatest challenges, satellite data is useful for just about any business.

From Uber and Apple to Tinder and Strava, most modern companies need access to orbiting satellites when boasting things like location tracking. For some time, governments held exclusivity when only hefty and pricey satellites were available. In fact, they’re burning cash even to this day. “It’s still costing large government operators like Airbus a billion to develop and get a satellite into space,” says Rob Desborough, investment director at Seraphim Capital, the spacetech venture fund. Even if entrepreneurs get their hands on these costly chunks of metal, government satellites take roughly seven and a half years to develop and launch, according to The Aerospace Corporation, the research and development centre. So when finally finished, they’re already out of date. “By the time it’s up there the technology is potentially already ten years old and then you’re going to keep it up there for a further ten to 15 years as well,” Desborough opines. Talk about a bad investment.

Enter spacetech startups cutting the costs by developing smaller satellites for as little as $1m, according to Desborough. “The industry is making previously extremely expensive and large satellite technology smaller in size, enabling more satellites to be launched due to lower mass,” says Rafal Modrzewski, CEO and co-founder of ICEYE, the satellite imaging startup. Indeed, with small satellites typically weighing under 500kg – and popular CubeSats even seeing below 10kg – they can be rolled out comparatively quickly, especially considering their low mass enables ride-sharing with other launches. “If you combine [low cost] with a new space approach of fast hardware development cycles, you can pump out satellites in a matter of months rather than years,” he adds.

Low cost and development time also make satellite constellations more achievable – in other words, multiple satellites sprawled across Earth’s orbit and linking up for consistent coverage. “When you have a much larger constellation with around 75 satellites you can really visit the same place on Earth every 15 minutes,” Desborough says. Moreover, due to their numerousness and cost effectiveness, it won’t be a disaster if a small satellite bites the dust. “If I’ve only got four satellites and I lose one I’m going to lose the quarter of my coverage,” the investor continues. “When I’ve got 70 then it doesn’t have the same impact so you can get new tech up more quickly.”

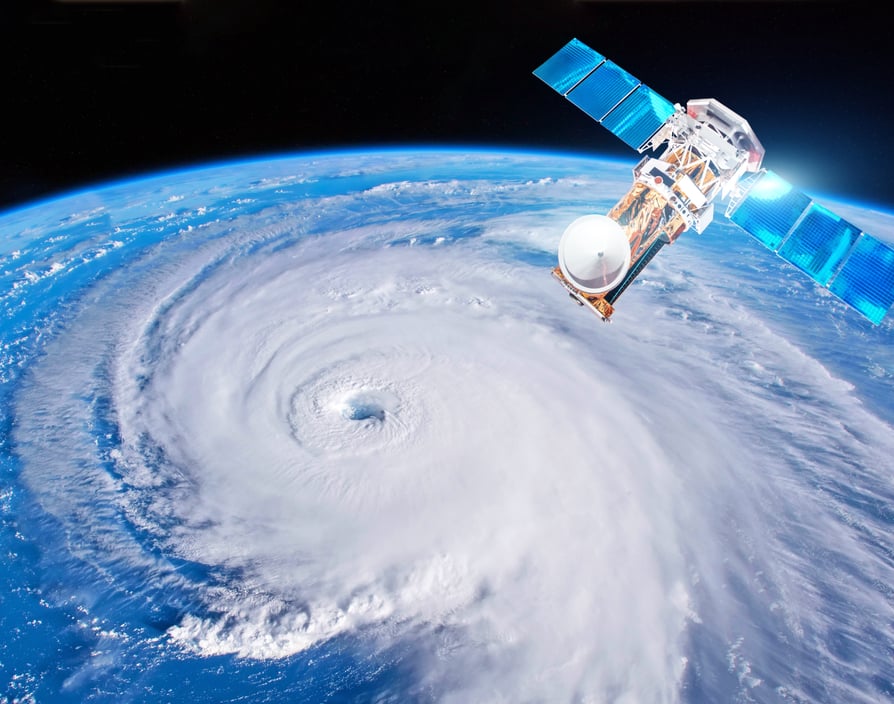

But their coverage does far more than just facilitate ride-sharing apps. In fact, small satellite data lets startups tackle hazards to humanity. “Big problems, such as illegal fishing, climate change and natural disasters, can be thwarted through the use of satellite data that is already being collected today,” explains Nick Allain, head of brand at Spire Global, the satellite data company. Satellite-harvested data is colossal and ranges from tracking weather patterns to mankind’s mark on Earth. The potential uses for this big data are so vast that satellite analytics will be worth $18.1bn by 2027, according to Northern Sky Research, the satellite and space market research company. “There is an infinitely increasing number of applications for the data that comes from satellites,” Allain promises. With small satellites, startups could be tapping into the goldmine.

It goes without saying the sky isn’t the limit in the tech’s funding landscape. “VCs are seeing the potential for a return on their investments and are eager to put their money into an industry that is seeing such dramatic growth,” Modrzewski says. In September 2018, for example, HyperSat, the small satellite platform, took home an impressive $85m series A round. Moreover, ICEYE bagged a $13m series A in August 2017 and a $34m series B in May 2018. “[That’s] largely due to our continued ability to deliver on our ambitious promises,” Modrzewski opines. Although most small satellite startups like ICEYE are yet to venture beyond their second or third VC round, it’s only a matter of time.

Through this prism, it seems big satellites are snookered by the benefits miniaturised ones bring and begs the question why they’re even still used. Well, given their size, small satellites can only pack so much punch. “For example, optical imaging like you see in spy movies requires a large lens and large sensor – which simply don’t fit into most small satellites,” Allain admits. Limited payload means small satellites can’t deliver quite the same results as larger ones, at least not outside constellations. “There are some cases where physics provide a unique challenge,” he says.

That includes finding ways to shrink even the most basic of satellite needs. For example, ICEYE tasked itself with rigging synthetic-aperture radar – fairly common remote sensing tech invented in the 1950s – to a satellite under 100kg and blast it into orbit. Not exactly rocket science by today’s standards but for a satellite that miniature, ICEYE say they were the first to successfully do it. “Quite a few experts were telling us early on that what we were aiming for was flat out impossible – and for good reason, it absolutely was very hard,” recalls Modrzewski. It means designers have no room to be picky with miniaturised satellites. “Hard choices need to be made about what you’re making – not everything you would like to have will fit your mass and size limitations,” he continues.

Even if your small satellite’s perfectly equipped to brave space, it won’t fly anywhere without launch capabilities and they’re not easy to obtain. “I think there are only 80 startup companies within the launch environments out there at the moment,” Desebrough explains. “So the issue here is not actually ‘have I raised enough money to build my first CubeSat and get it into orbit?’ It’s actually then finding the capacity with someone like SpaceX as well.” Brilliantly, Britain’s working to solve this problem. In July 2018, the UK and the Scottish government set aside £31.5m to construct Britain’s first spaceport in Scotland by 2020, with a view to launch 2,000 small satellites from it by 2030. “You’ve definitely got an industrial strategy around space in the UK,” Desborough says.

However, Britain isn’t the only power looking to claim a piece of new space turf. “Increasingly, we’re seeing the same in Luxembourg, Abu Dhabi etcetera where they’re looking to diversify the economy,” Desborough says. Sweden and Norway, for instance, are vying to steal the march from Britain and ease Europe’s blast-off challenges with their own spaceport in Lapland. Such global buzz is a result of nations realising the tangible benefits spacetech brings right now, rather than just for the future. “Whether you are powering real-time premium adjustments for the insurance industry, maritime navigation or mining for oil and gas, satellites affect all of these industries,” Desborough summarises.

From promising funding to Britain’s spaceport blueprints, the stars are aligned for small satellites to iron out their payload issues and become the go-to for many industries. “Based on what the industry is looking like right now, the future of [small satellites] will see growth, both from an investment side and launches,” Allain says. And by combining the power of traditional satellites and agility of small ones, the stage is set for the tech as a whole to reach some seriously impressive heights. “New space companies will join forces with traditional companies to drive innovation and build satellites that can change how we access space and deliver data to people all over the world,” Allain concludes. ![]()

Share via: