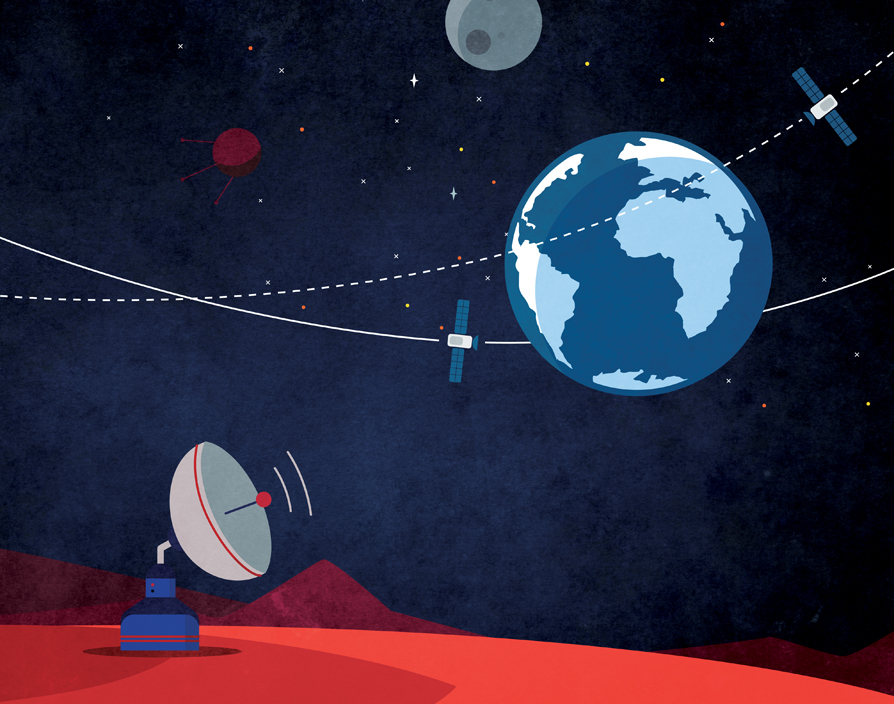

Public interest in outer space has never been greater on these shores. But while many people have been celebrating the exploits of British astronaut Tim Peake and the triumphant return of Star Wars, what’s happening just below the surface is arguably more exciting. Better access to big data combined with declining launch costs have opened space up to smaller players – and they are harnessing it in ways that were previously unimaginable. “Space is becoming more privatised and much smaller things are being put into orbit,” says Joyeeta Das, co-founder and CEO of Gyana, the space-technology company. “That’s essentially making it much easier for small and medium-sized businesses to participate.”

It’s certainly a far cry from the days when space was seen as the preserve of national governments. “The industry is going through a process of democratisation, where disruption is skewing things toward commercial applications,” says Mike Lawton, founder and CEO of Oxford Space Systems, the developer of low-cost deployable space structures. “That means we’re seeing smaller missions, more aggressive timeframes and a willingness to embrace innovative, risky technology.”

This transformation has not gone unnoticed by the British government, which is looking to more than treble the size of the UK’s space sector to £40bn by 2030. And this doesn’t just encompass companies that are helping put astronauts into orbit. “Space can and does support so many other sectors; things like agriculture or financial services,” says Colin Baldwin, UK Space Gateway programme manager at the UK Space Agency. “As a nation, we are trying to join up all of these dots and make people understand that space is relevant to everybody, everyday.”

In many respects, the UK is the perfect place from which to launch a space startup. “There are fantastic universities and talent here and they are developing some amazing technology,” says Corentin Guillo, founder and CEO of Bird.i, which is delivering real-time satellite imagery to the mass market. “That’s something you need in order to build any type of business in the space sector.”

Britain also has a space hub to be reckoned with in the shape of Harwell Campus. Located in the heart of Oxfordshire – and home to the UK Space Agency – the campus is connecting academics and startups with established players in a bid to drive the sector towards its £40bn target. “What Harwell offers is the ecosystem to actually accelerate that contact between small and large organisations,” says Dr Barbara Ghinelli, business development director for the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) at Harwell Campus.

But that’s not to say the best innovations are all emerging from the southern reaches of the UK. In Scotland, the likes of Clyde Space and PocketQube Shop are pioneering the miniaturisation of satellites, which is opening up a whole host of opportunities for companies and consumers alike. “If you can miniaturise the technology, the cost to getting something into orbit is so much lower,” says Tom Walkinshaw, founder and CEO of PocketQube Shop. “That means you can disrupt massive industries and start looking at use cases that previously weren’t possible.”

And it’s this appetite for disruption that makes startups such a key part of the space industry’s future. “It’s very important we bring innovative solutions that are small, that impact the life of regular people and that are the result of direct upstream and downstream space technology,” says Das. “It’s not just about SpaceX and massive things like that.” In fact, the sector’s big hitters are becoming increasingly dependent on the work being done by the smaller players. “Some of the big names in Europe have openly said to us that they look towards SMEs to undertake the risk of genuinely disruptive technology,” says Lawton. “We are de-risking the scary new stuff for them.”

Predictably, the innovations emerging from Britain’s space sector haven’t gone unnoticed by the investment community. “It no longer takes ten, 20 or 30 years to develop your technology; you can do this in a matter of three, four or five years,” says Guillo. “From an investment perspective, it’s much more attractive because you know you can invest in a company that could exit in a reasonable timeframe.”

Moreover, with big data becoming bigger business by the day, there’s enormous value in the information that’s been drawn from space. “You won’t believe the amount of data we already have from space,” says Das. “We are sitting on a resource that is already there, that doesn’t cost anything and that is dying to show a use case. That’s a very compelling opportunity for investors.”

The government is also stumping up capital for ambitious space startups through Innovate UK. As well as offering grants to help get businesses off the ground, last year’s Space Mission saw Innovate UK fly nine companies out to the States to seek investment and meet some of the industry’s heavyweights. “Being exposed to what was happening in the US really helped us accelerate the positioning of Bird.i,” says Guillo. “But the most important aspect was access to finance; it was an opportunity to pitch to investors and start making some connections.”

However, UK space startups still face a number of challenges when it comes to funding. As it stands, only 20% of government money is available through Innovate UK, with the remaining 80% committed via the European Space Agency (ESA). While bodies like the Satellite Applications Catapult are doing their bit to help companies secure vital funding from the ESA, Lawton says it has been one of the biggest barriers to growth for Oxford Space Systems. “The ESA struggles to work with highly innovative, fast-moving companies because it is risk-averse and doesn’t understand disruptive business models,” says Lawton. “That essentially puts a brake on the industry.”

Another challenge facing the industry is space pollution. With companies launching ‘mega constellations’ of small satellites, outer space could soon find itself clogged up with even more debris. “If the world wants to exploit space in a sustainable way, we need to find a way to get rid of the satellites that are not being used anymore,” says Guillo. “Otherwise it will be too crowded and risky to launch anything.” Thankfully, the ESA, along with a number of other companies, are busy working on solutions to this problem. “That’s another industry that’s already starting to grow,” says Das. “It’s looking to clean up the space industry.”

In spite of these obstacles, the future looks bright for the British space sector. And its place on the map will surely be cemented when Europe’s first spaceport opens on these shores. “That will show that the UK is serious about space,” says Baldwin.

Flying high

Bird.i

Corentin Guillo first had the idea for Bird.i while working in the French space industry. It was a time when Google, Yahoo and Microsoft were releasing their own mapping applications and the likes of Airbus were supplying the sector with real-time satellite imagery. “I always had this vision of bringing these resources into the reach of individuals and businesses,’ says Guillo. However, he soon realised this wasn’t a vision he could bring to life in his native country. “I discovered very quickly that it would never happen in France because of the state of the industry,” he adds. “That’s why I decided to move to the UK. The mindset of this country is much more open.”

While working at the Satellite Applications Catapult, Guillo was able to access the finance he needed to get Bird.i off the ground and demonstrate it to customers. The company then became one of 90 startups to be inducted onto Mass Challenge UK, the accelerator programme. Not only did this help Guillo get to grips with pitching to investors and forging an effective marketing strategy, it also hooked him up with some business mentors. “That was really important because as a startup, you need to access people with experience who will help you succeed,” says Guillo.

The company is now working closely with drone and satellite providers to make real-time satellite imagery available to the mass market. By way of example, Guillo says having access to this imagery could allow a construction company to monitor the progress of its building sites in real-time. Alternatively, a holiday-goer could check whether the online description of a hotel really stacks up. “By showing you the latest imagery, you will know that if you book this hotel today and you go there next week, this is exactly what you will find,” says Guillo. ‘It’s really about making this imagery a part of your life.”

Inside knowledge

Gyana

Gyana is a great example of how space can breathe new life into big data. The company started to take shape while its co-founder and CEO Joyeeta Das was studying for her MBA at Oxford; a government-funded trip to the Kennedy Space Centre saw her spend some time with NASA, as well as industry heavyweights Virgin Galactic and Lockheed Martin. “I got to see up close and personal what these guys are doing,” says Das. “And I found that there are still a lot of things that we can do with big data and space.” Suffice to say, it got her entrepreneurial juices flowing. “I couldn’t have been an astronaut but I thought I could maybe make a good space entrepreneur,” she laughs.

Before long, Das had brought Gyana’s two co-founders on board; Andrew Li, her MBA classmate, joined as COO, while her husband David Kell, also from Oxford, assumed the role of CTO. And, with some serious academic and engineering credentials behind it, Gyana set about developing its groundbreaking tech. Bringing emotional intelligence together with deep learning, machine learning and satellite imagery, it can identify how people in a particular place are feeling at any time of the day, while also providing data on transport infrastructure and trends such as crime rates. “There are many things we want to know about a place when we are looking down on it from above,” says Das. “What we are trying to do with Gyana is bring that to life.”

Raising its first seed round from a VC in Chicago in May 2015, Gyana extend this to $3m in November and has already ploughed over $1m into product development. It is now targeting a Series A raise of $20m before the end of 2016, which will come from investors in both the UK and Silicon Valley. “The money we are raising right now is to scale up the product,” says Das. “We want to take Gyana to everybody.” ![]()

Share via: