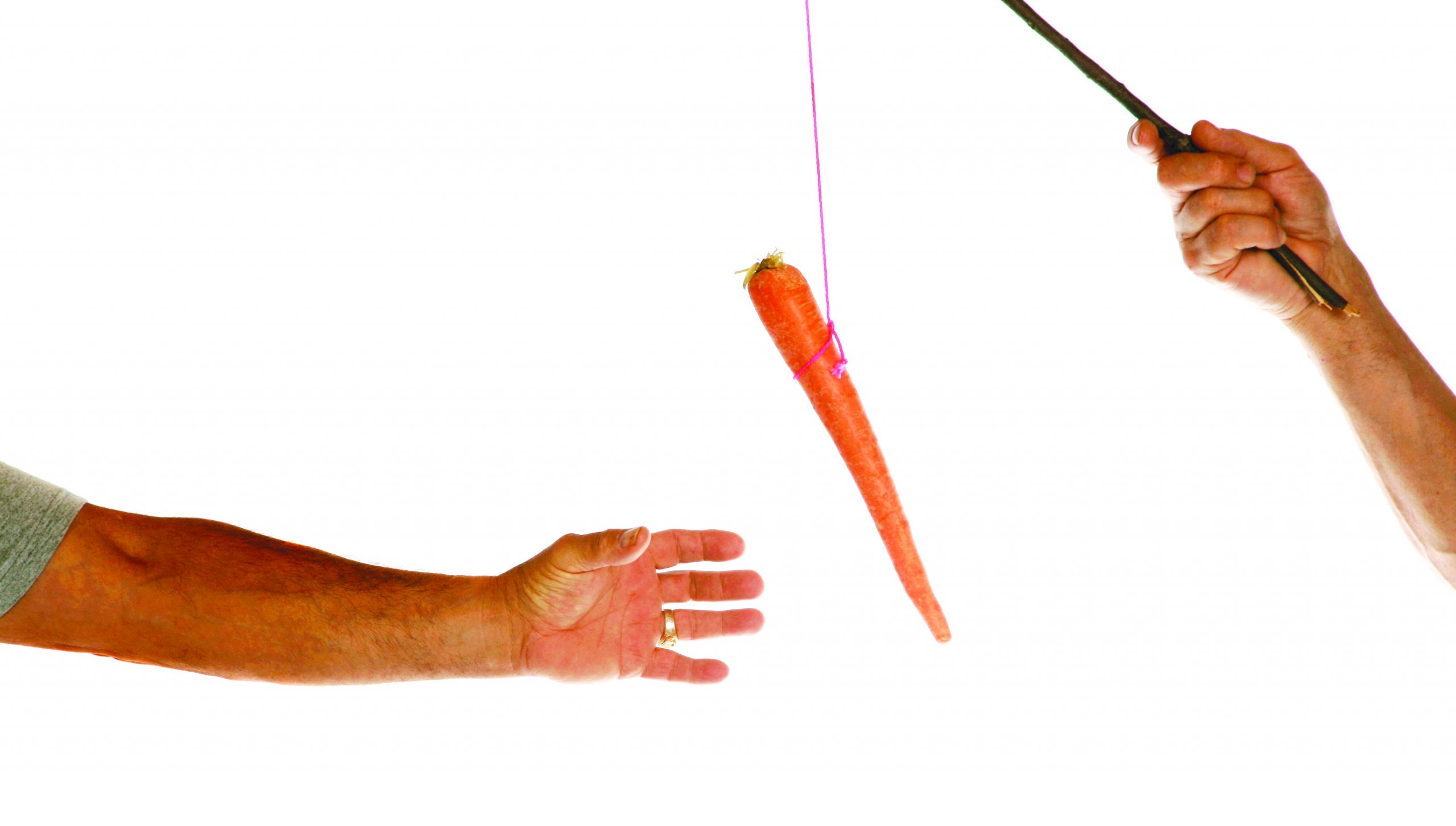

Share-incentive schemes can work for all sizes of businesses. However, sometimes for smaller ventures it can pay to be a bit more creative. We’ve heard of share-incentive schemes involving pies and beers, but sometimes it’s better to look at tried-and-tested formats to sort the wheat from the chaff.

There can be no one-size-fits-all approach to incentive schemes, so they inevitably vary from company to company. One of the classic examples is that of John Lewis which, by trading as a partnership, has done away with traditional share holders in favour of direct incentives. As with any company that operates incentive schemes, John Lewis is entitled to dictate certain terms; the standard scheme doesn’t allow partners to hold onto the shares past the end of the tax year, instead paying out all of the dividends at its close. Despite this, partners maintain a voice in the company and the John Lewis model perhaps features share incentives at their most effective.

So how do they work? Share incentives come in four basic types. First of all are free shares. Free shares are given by an employer, often in recognition of high performance. A business can award £3,000-worth of free shares to an employee in any given tax year under a Revenue-approved Share Incentive Plan (SIP) without any initial tax charge.

Another possibility under an SIP is partnership shares and, as the name suggests, these reflect an investment on the part of the employee. An employee can take 10% of their total salary for the year in shares up to a maximum value of £125 a month. As this investment comes before tax, long-term investors can use this to save tax and national insurance contributions on a portion of their income. These are closely linked in with matching shares, which are like-for-like shares awarded by a company; a business can award up to two shares for every one that an employee buys with their gross income.

Finally, as shareholders under an SIP, employees are entitled to dividends and, if the employee chooses, the company can award these as dividend shares, up to a maximum value of £1,500 a year. Again this offers tax benefits over a standard dividend payout depending on the length of time the member of staff holds onto the shares.

As already mentioned, all purchases through an SIP come before tax, meaning you aren’t liable to pay tax when first obtaining them. Whether you have to pay tax and National Insurance contributions on the ultimate value depends on how long you have held the shares – for free, partnership and matching shares, if you remove shares from the plan in the first three years after purchase you will be obliged to pay income tax on their value at exit. If you remove them between three and five years you will be required to pay tax on the lower of their value at purchase and their value at exit – this means that if the share value has decreased since purchase you won’t be penalised in terms of your tax.

But why offer incentive schemes? Because there is a mutual benefit. It allows employees valuable tax breaks while offering them a good reason to stay invested in a company. Aside from the fact that holding onto the shares for over five years offers the best value return, in times of growth they will have a very strong reason to remain with your company as their shares will be increasing in value. From your perspective, you are freeing up capital in the short-term and also saving your National Insurance contributions; this can prove invaluable. As David Reuben, share plans director at Postlethwaite & Co, says: “If you would be paying out £100,000 in bonuses but make allocations under an SIP instead, it has initially saved the employer £100,000 plus National Insurance.”

Obviously, there are limits, however. Given that you are effectively offering cheap shares to your employees, there are only so many shares you can give out without to some extent affecting your stock. “It saves on cash but it’s paid for by all of the shareholders essentially by dilution,” Reuben remarks. However, with most companies, it will be generally understood by investors that a certain proportion of the shares will be used for employee incentives. “As long as you don’t go over what’s understood to be the limit, which for listed companies is about 10% over a 10-year period, then it shouldn’t reduce the value of the shares,”

Unfortunately, not all businesses utilise incentives in the best way. An Elite source explains: “Working at a bank in the autumn of 2008 was hardly the safest bet, employment-wise,” he explains. “The credit crunch meant none of us felt that secure in our jobs.” So when management came around and suggested staff might like to take shares over a proportion of their wages it’s not surprising that nobody exactly bit their hand off to take the offer. “They were asking us to take less money when we needed it most and take share options that were looking very shaky just so they could shore up against their financial problems,” our source concludes. An example of how not to do it, perhaps. ![]()

Share via: