Public sector procurement is a burdensome process. Its detractors, of which there are many, will tell you it is painfully bureaucratic, complex and expensive. And nowhere is this encumberance felt more than amongst the SME community. But change may be afoot. Last February the cabinet office laid out plans to make life easier for SMEs with an eye on the public sector prize, and has followed up since with more policy changes. But have they had any real impact?

Government has a lot to gain from working more closely with SMEs. Not only can smaller firms be more flexible and nimble afoot, they are often cheaper because they don’t come with the same costs – salaries as well as associated overheads such as travel, office space etc. What’s more, by their very nature, they are often more innovative and can offer unique, bespoke solutions.

What’s more, it’s good for the economy if the nation’s entrepreneurs get their mitts on a bigger slice of the public sector pie. Government expenditure on procurement amounts to some £236bn annually. This means that just a 1% increase in contracts awarded to SMEs, rather than their big, burly competitors, would represent an extra annual investment of £2.3bn in smaller organisations.

And on the flipside, the lure of government contracts is no great mystery. It is guaranteed income over a sustained period of time. A £60m contract over five years? That would put a few zeros on the P&L.

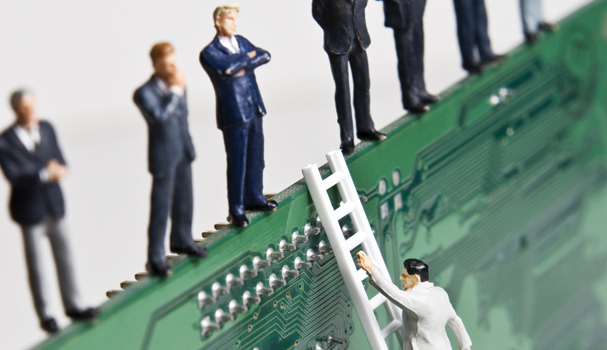

But there are many challenges to navigate if an SME is to stand a chance of winning government business. Firstly, the process is complex and time-consuming. Larger rivals will put teams of people to work on the tender for a single piece of work, whereas an SME may only be able to afford one full-time resource, if that.

Brian Taylor is the co-founder of PixelPin, a technology company that replaces passwords with pictures, but has worked as a freelance consultant for the best part of two decades. Unable to gain access to work directly for government, Taylor worked in-house at firms such as General Dynamics and BAE. As a result, he has worked on highly lucrative tenders. “I’ve done two bids for £1bn contracts and I lost one and won one. In both cases, the teams were substantial and we were spending many hundreds of thousands of pounds on the government bid.” There aren’t likely to be many small businesses in the land that can compete on that kind of scale.

The obvious answer is to dip a toe in the water; it often makes more sense to go for smaller, labour- and resource-intensive contracts. Sara Murray is the founder of buddi, a tracking device which is now used by about 25 police forces nationally, 85% of local authorities and a few NHS trusts. Users range from former offenders as well to vulnerable people such as the elderly and dementia sufferers. Murray points out that if small firms do their homework and target the smaller contracts, they stand a good chance of being successful. “For things that fall under the OJEC [Official Journal of the European Community] threshold [currently set at around 170,00 euros] it’s very easy for authorities to buy them. They can easily go out and spend £50,000, or, in fact, any amount up to the threshold. Which is not an insignificant amount for a small business,” she says.

Another way for smaller companies to gain access to large contracts when they lack the in-house resources, is to buddy up with a larger organisation. Many companies will bid for multiple contracts; some as sole traders, others with a larger, corporate partner.

Unlike many of her peers, Murray says she doesn’t have a problem with the complexity of the procurement process. In fact, she says it’s necessary. “People complain because as they get into more high value procurement, the process becomes more and more complicated,” she explains. “But if you’re buying something more valuable of course you should take care over buying it.”

Yet Murray does agree that the process is often unnecessarily time-consuming. “I’ve done deals with large corporations that are far larger than anything we’ve ever done with public procurement which have happened very quickly.” The reason for the delay in the public sector is often because government doesn’t have a clear understanding of what it wants to purchase at the beginning of the process, she says. This means it has also been bad at encouraging innovation, argues Murray. “The government hasn’t gone and found anything new and different.”

It is for precisely this reason that pre-tender engagement is vital, says Murray. “The cabinet office has been really encouraging procurers to talk to companies before putting procurements out to help them understand a bit better,” she explains. The cabinet office’s Stephen Allott, who is the crown representative for SMEs, says that pre-procurement engagement works both ways. “SMEs need to be part of the conversation,” says Allott. “When the government is deciding what they want to buy and setting the specifications, having informal engagement with that process [is key],” he explains. “Quite often there are PINS (prior information notices) which are published explaining how businesses can get involved with that process so that they can engage with the early stages of procurement.”

Richard Bennett, co-founder and MD of Updata Infrastructure, a WAN and managed services provider to local authorities and government, says the importance of building relationships with potential government clients cannot be over-emphasised. “If you see a tender that’s come out and you haven’t spoken to that customer beforehand, then don’t waste your time,” he says. “If you want to improve your win rate, the best thing you can do is talk to customers before they come out to tender.”

One of the advantages of bidding for government work is that information about the contract is usually readily available under the freedom of information act. “You can glean a lot of information about who the current supplier is, how much they’re being paid, when’s that contract coming to an end, what’s the likelihood of an extension, or what’s the extendability of the contract,” explains Bennett. “In our sector there’s quite a lead time between getting replacement from one to another, so we would probably be out there talking to the procurer about two years before the contract was scheduled to come to an end,” he says.

Another piece of advice offered by the technology entrepreneur is to ensure that the team tasked with managing the relationship isn’t overly pushy in their approach. “It’s about being consultative, not trying to sell,” he says. “The sales people we’ve had to let go of have been the ones who wanted to push something down people’s throats and were lacking the consultative side.” Taking a different approach to that which would typically be used in the private sector has certainly helped bolster Jamie Waller’s business, JBW Group (see box).

Once small firms have mastered the right approach, they need to make sure they are doing their utmost to secure the best score on the tender documents. “SMEs that are new to government [contracts] don’t realise that the tender process is like taking an exam,” explains Allott. “You can be the best at doing something in the world, but unless you put the answers down on paper during the exam, you won’t get any marks. SMEs have got to learn how to do these formal processes,” he says. What’s more, if small companies don’t have this expertise in-house, they should seek external guidance, Allott urges. “Bring your tendering skills up to first-class standard by getting help.”

As with many things in business, getting a foot in the door is the hardest part. Not least of all because many procurers will want government references. Therefore, winning the first government contract, however small, could be the beginning of a new, lucrative, phase in your company’s history. “When you get your first contract, forget about profitability,” says Waller. “Run it as a cost; run it at a loss. But do the most exceptional job of it to get the most exceptional government reference. Then the following year you can win four or five of them.”

But there is only so much small firms can do themselves – they also need a steer from government. And since Allott took up residence at the cabinet office last february, he has had a firm hand on the tiller. One of the landmark changes was the introduction of the ‘mystery shopper’ initiative – a way for SMEs to raise concerns about public procurement processes. “Suppliers can report directly things they think are not going right and the cabinet office can intervene and do something about it,” explains Allott.

There have been other changes that have attracted less attention. One of the biggest barriers to entry for many SMEs historically was the requirement of three years of audited accounts in order to show the supplier had the financial prowess and sustainability to handle large contracts. This is no longer a requirement for central government contracts, says Allott. “That’s not a rule anymore, so if your readers see examples where they’re still being asked for three years of accounts, they can report that to the mystery shopper service.” Another rule dictating that companies’ turnovers needed to be four-times the contract size has also been jettisoned. “Again, if readers come across financial thresholds, they can report that to the mystery shopper service and we’ll get it changed.”

Whilst there weren’t any figures available at the time of going to press as to whether or not the number of government contracts being awarded to SMEs have improved, certainly, the headlines seem to suggest that things are looking up: at the end of 2011, Yorkshire-based Redfern Travel was awarded the government’s domestic travel contract worth £1.1bn over 15 years. And more recently, Leeds company Calder Conferences beat off stiff competition to secure the contract to manage central government meetings, thought to be worth £10-12m.

But what’s the word on the street? It’s true to say that opinion is divided – and often not in government’s favour. Waller, Taylor and Bennett are all fiercely critical of a process they see as being wildly outmoded and unnecessarily complicated. But there are rare voices of support for the cabinet office’s attempts to make SMEs’ lives easier. “This really is a time of change,” says Sara Murray. “There is now a whole team of people who have commercial backgrounds and know where the want to take the government procurement process to make it easier for SMEs.”

Nonetheless, Murray is hesitant to suggest that the government will meet the target it set itself of 25% of public procurement to be from SMEs by March 2015. “I agree that they’re likely to be way off target,” she admits. “But if you don’t set targets, you don’t get anywhere.”

Going for gold

Having proven unsuccessful in early attempts to gain access to public sector contracts, Jamie Waller, founder and CEO of bailiff firm JBW Group, decided it was time for a strategy overhaul. “In the first three years of JBW, we found it really difficult to get to grips with public procurement. Then we decided that, actually, what we don’t need is a team of 30 salesmen; what we do need is great writers,” Waller explains. “We invested in a team of mainly ex-journalists, and other people with great writing abilities.”

The bet paid off. JBW has gone from not winning a single government contract in its first three years, to a 100% hit rate in 2012. Not that he expects this run of good fortune to continue indefinitely. “I have to say, it’s highly unusual. It’s the only time in history I believe that us or one of our competitors have had that kind of strike rate. We wouldn’t expect that to continue.” Neither does he expect it to drop too low, either. “Since we decided to invest in people rather than salesmen, it’s always been above 50%,” he says.

Once the right team is in place, it is also key to play to your strengths, says Waller. “Pick your battles. You can’t go for everything.” Also, one of the key advantages JBW has over its larger rivals is that it is nimble. “The government does want to see flexibility, it does want to see businesses that can be dynamic, and it also wants best value opportunities,” says Waller. “My experience is that the government is totally pissed off with the big FTSE players bidding with a price of X and then every single change that’s required during the course of the contract, putting in prices that are three times what they were proposing at the beginning.”

Part of the challenge is ensuring that a SME can get this across on paper. “The forms are very technical,” says Waller. “You need to look carefully at the scoring mechanism as well as how they’ve laid out the questions.”

If a small firm can get all of this down on paper, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t win government work, says Waller. “As an SME you can be dynamic and you can give them added value throughout the terms of the contract without penalising them. Why wouldn’t they choose you?” ![]()

Share via: